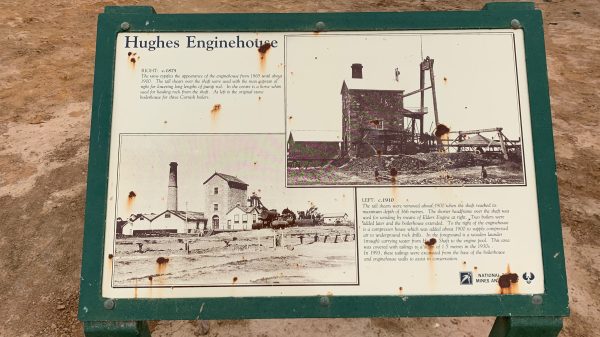

The historical significance of Hughes Engine House

The Hughes Engine House stands as one of South Australia’s most significant industrial heritage sites.

Constructed in 1865, this remarkable structure played a vital role in the growth of Moonta and in the Moonta Mines’ copper mining operations, which ranked among the British Empire’s largest copper producers.

Architectural Marvel and Construction

The limestone construction of Hughes Engine House showcases exceptional craftsmanship from the 19th century. The structure features distinctive architectural elements characteristic of Cornish design, including robust walls and an impressive chimney stack that dominates the landscape.

Technical Operations

The Cornish beam engine within Hughes Engine House represented cutting-edge mining technology of its era. This powerful machinery, installed under Frederick May’s supervision, operated continuously for 58 years until 1923. The engine’s primary function involved pumping water from depths reaching 700 metres, enabling access to the rich copper deposits of the Elders Lode.

The installation of this sophisticated equipment required an investment of £7000, equivalent to several million dollars in contemporary value. This substantial investment highlighted the strategic importance of the Moonta Mines operation.

Present-Day Heritage

The Hughes Engine House remains a cornerstone of the Moonta Mines State Heritage Area. Following its closure, the National Trust undertook significant conservation work in 1973, ensuring the preservation of this remarkable industrial heritage site for future generations.

Leave A Comment