Red Fort

Inside the walls of India’s most powerful fortress

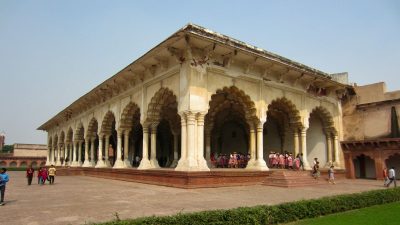

The Red Fort (also known as Agra Fort) is one of India’s most significant historical monuments, showcasing the grandeur of Mughal architecture and power.

This UNESCO World Heritage site spans an impressive 94 acres and tells the tale of multiple dynasties that shaped Indian history.

The Red Fort’s story begins well before the Mughals, though its most celebrated chapter started after the First Battle of Panipat in 1526. When Babur emerged victorious, he chose this strategic location as his residence, setting the stage for the fort’s transformation into a symbol of Mughal might.

The fort gained prominence when Humayun was crowned within its walls in 1530. However, the structure truly flourished during Akbar’s reign. Recognising its strategic importance, Akbar arrived in Agra in 1558 and initiated an ambitious renovation project that would change the fort’s destiny.

The magnificent transformation

When Akbar discovered the original brick structure, known as ‘Badalgarh’, it was in ruins. His vision transformed the Agra Fort into an architectural marvel. The emperor commissioned red sandstone from Rajasthan’s Barauli area, creating the distinctive crimson facade that earned it the name Red Fort.

The construction process was remarkable:

- 4,000 workers laboured daily

- The project spanned eight years

- Completion occurred in 1573

- The design incorporated both bricks and sandstone

The Red Fort underwent another significant transformation during Shah Jahan’s reign. Unlike his grandfather Akbar’s preference for red sandstone, Shah Jahan favoured white marble, introducing a new aesthetic to the fort’s architecture. His additions created a striking contrast between the original red sandstone structures and the elegant white marble pavilions.

Imperial drama and decline

In a twist of fate, the Agra Fort became Shah Jahan’s prison when his son Aurangzeb seized power. The emperor spent his final days gazing at his masterpiece, the Taj Mahal, from the Muasamman Burj tower’s marble balcony.

The fort’s significance extended beyond the Mughal Dynasty. The Maratha Empire captured it in the early 18th century, marking the beginning of a turbulent period. The fort changed hands several times before the British took control during the Second Anglo-Maratha War in 1803.

The historical fort played a crucial role in the 1857 rebellion, which ended the British East India Company’s rule and ushered in the British Raj. Today, parts of the Agra Fort remain under military control, housing India’s Parachute Brigade.

Continued cultural impact

The Red Fort remains a remarkable example of Mughal architecture and engineering. Its double ramparts, massive circular bastions, and intricate details showcase the sophisticated building techniques of medieval India. Located just 2.5 kilometres from the Taj Mahal, this historical fort continues to draw interest from around the globe.

Leave A Comment