Sandakan Memorial Park

A story of survival and remembrance

- Remnants of camp buildings

- The memorial pool

- The walkwayy leading down from the information entre

- Old machinery from WW2

- THe memorial

- One of many information stones in the park

- Three of the Death March surviors

- A peaceful glad in the park

- One of the excavators used by the POW forced labour

The Sandakan Memorial Park in Borneo holds a profound place in Australian military history.

This peaceful garden serves as a reminder of one of the most tragic events of World War II in the Pacific region. Located in the Malaysian state of Sabah, the memorial grounds mark the site of the former Sandakan prisoner of war camp.

Historical significance

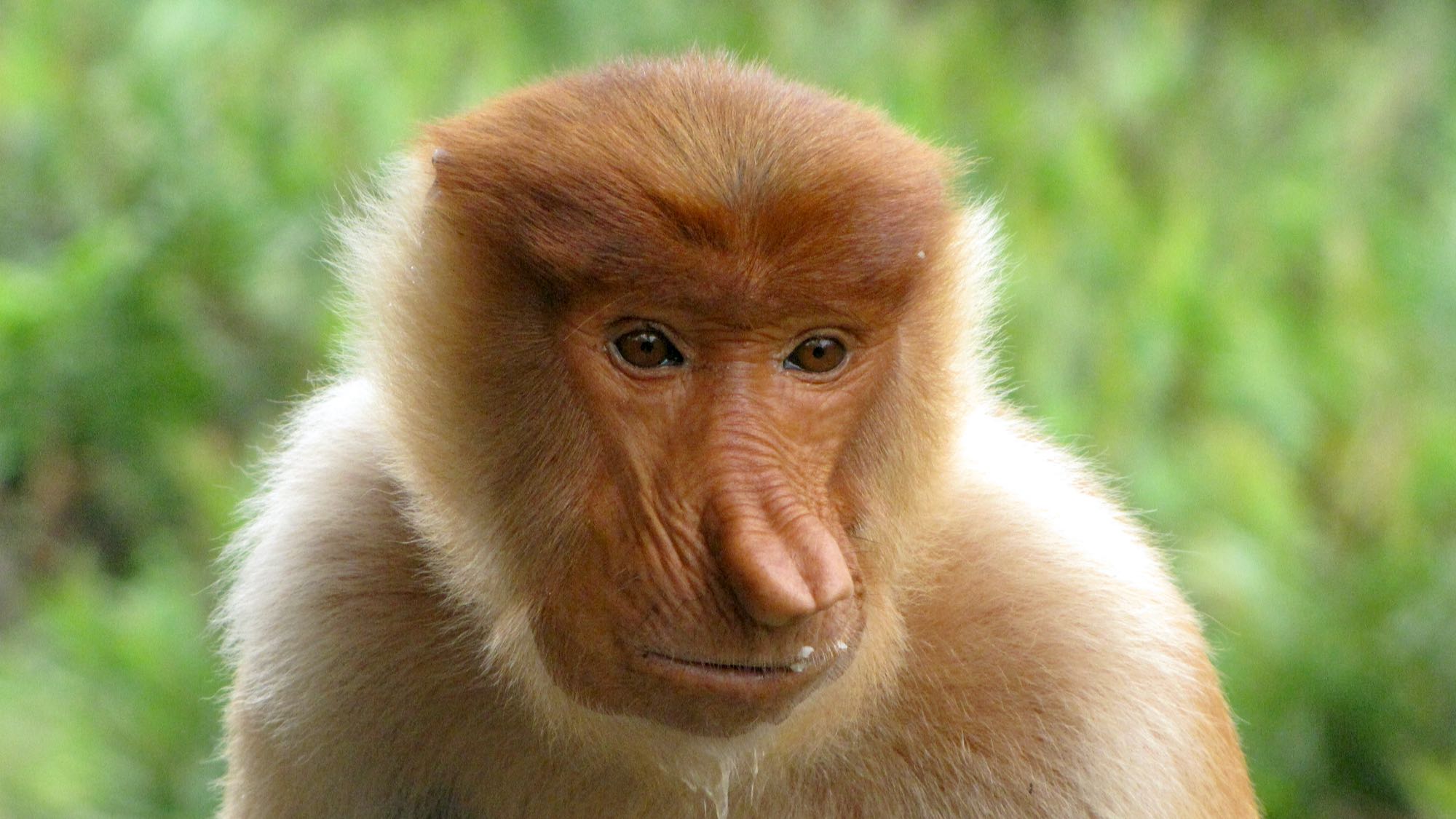

During the Japanese occupation of Borneo, approximately 2,700 Australian and British prisoners of war were held at this location. The prisoners endured harsh conditions while being forced to construct a military airstrip. The camp operated from 1942 to 1945, becoming a dark chapter in WWII history.

The POWs, weakened by malnutrition and disease, worked tirelessly in extreme tropical conditions. By late 1944, Allied bombing had destroyed the airstrip, and the Japanese military began planning the movement of prisoners inland.

Wartime conditions in the camp

The documented conditions at Sandakan POW camp reveal a story of extreme hardship. The camp, originally built to hold 1,000 prisoners, eventually imprisoned more than 2,700 Australian and British POWs. The prisoners were housed in barracks while being forced to construct a military airstrip using basic hand tools.

By 1945, the prison population faced severe malnutrition as food rations were drastically reduced. Disease was widespread, with many prisoners suffering from malaria, dysentery, and tropical ulcers. The camp’s limited medical supplies made treatment nearly impossible for the POW medical officers.

The deteriorating conditions worsened after Allied bombing damaged the airstrip in late 1944. The Japanese captors reduced rations further, and physical abuse of prisoners increased. When the death marches began in January 1945, many prisoners were already too weak to survive the journey.

The Sandakan Death Marches

The Sandakan death marches represent one of the greatest tragedies in Australian military history. Between January and June 1945, the Japanese military forced approximately 1,000 Australian and British POWs on three separate marches through Borneo’s rugged terrain.

- The First March: In January 1945, 470 prisoners began the first march to Ranau. The POWs, already severely malnourished, trudged through dense jungle carrying heavy loads of ammunition and supplies for their captors. Those who could not continue were killed. Only 190 prisoners survived the initial journey to Ranau.

- The Second March: In May 1945, 536 prisoners began the second march. With monsoon rains creating treacherous conditions, the prisoners battled extreme exhaustion, tropical diseases, and brutal treatment. Fewer than 70 prisoners reached Ranau alive.

- The Final March: The third march in June 1945 involved the last remaining 75 prisoners at Sandakan. Aware of Allied advances, their captors forced these men on what would become a fatal journey. None of these prisoners survived.

Of the six Australians who survived the Sandakan death marches, all managed to escape into the jungle where local people provided them with food and shelter at great personal risk. Their testimonies later proved crucial in documenting these events.

Memorial features and monuments

- Modern Gardens: The grounds contain beautifully maintained gardens with native plants, creating a respectful atmosphere for reflection.

- Commemorative Pavilion: A central pavilion houses information about the camp’s history, including photographs and personal stories of the prisoners of war. Display cases contain wartime artifacts and maps detailing the march routes.

- Memorial Walls: Stone walls display the names of those who lost their lives, ensuring their memory lives on for future generations. The walls list 2,434 Australian and British military personnel who died at Sandakan and during the death marches.

- The Commemorative Pool: A reflection pool provides a peaceful space for contemplation, surrounded by plaques sharing survivors’ accounts of their experiences.

Preserving the memory

Annual commemoration services take place at the Sandakan Memorial Park, bringing together families of former POWs and military representatives. These ceremonies help maintain the connection between Australia and Malaysia while honouring the sacrifices made during WWII.

The site continues to play a vital role in historical research and education. Archaeological studies have uncovered numerous artifacts, providing insights into camp life and the prisoners’ experiences.

Practical information

- Opening Hours: Daily from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm

- Entry Fee: Free admission

- Dress Code: Modest attire recommended (covered shoulders and knees)

- Location: Mile 8, Labuk Road, Sandakan, Sabah, Malaysia

- Transport: 15-minute taxi ride from Sandakan town centre

- Facilities: Information centre, restrooms, parking, wheelchair access

- Best Time to Visit: Early morning or late afternoon to avoid heat

- Guided Tours: Available with advance booking Special Access: Group tours should be arranged in advance

- Brochure: Sandakan memorial Park PDF

A beautiful peaceful place very well done. When you think of the terrible things that happened here.lovely grounds to stroll round and informative display and film

This is part of our & Malay sad WW2 history. It is profound in personal effect. The stories and memorial is so sympathetic to those who lost their precious lives at the hands of theJapanese forces during WW2. It is hard to imagine that this now peaceful and serene place was such an horrendous experience for thousands of the soldiers who sadly found themselves here as victims of war. It is a testament to their memory.

I have to admit that I struggled when I came here. My father was stationed in Sandakan at the end of WW2 to help with the clean up of the occupations. I can only imagine what he saw. He never spoke of it.

Had a short visit here today. Very moving and the information in the building with the photos and details very instructive. Very very moving.

We were very glad we made the taxi ride to this park as the history of what occurred in Borneo during the Second world war must never be forgotten. The park is very tranquil but as you read the guide signs the horror of what took place there and in the countryside are very informative and moving.

A memorial site built in the former grounds of the former POW Camp, which housed 2500 Australian and British soldiers who were brought by the Japanese after the fall of Singapore in February 1942 to build an airstrip. Sick, weak, starving, and over-worked, they were forced over three interminable periods to stagger across 250 kilometres from Sandakan to Ranau. By the end of the war, only six Australians survived, after escaping into the jungle and being helped by local people.

A beautiful memorial to those who endured the Sandakan death march. A little piece of Australia within Borneo.

As an Australian, this is a must visit. It covers the death marches of the Australian & British soldiers during WWII, it is so informative & I am embarrassed to say it, this was such a huge educational experience for my whole family, because unfortunately, our schools do not teach us our history of the wars only invasion /settlement of Australia.

Wow. Again reminded of the depths humans can stoop to. Unbelievable cruelty on one hand, and strength with humanity on the other.

And we never seem to learn Suzy

A very humbling place. The grounds are well presented and the information you can learn here is heart breaking. Definitely worth visiting and paying your respects.

A memorial place worth visiting while in Sandakan. Such tragic (maybe an understatement for me to say) to know how these brave men endured the ugliness of war.